You may have seen in newspapers and on websites over the past few days, a dog named Frankie who can supposedly sniff out thyroid cancer. What is especially great about this story is the high rate of success shown by good-old Frankie, correctly detecting cancer in 88% of cases. So just how does a dog go about sniffing out cancers? Does cancer give off a particular smell? And could this be used in the world of cancer diagnostics?

Getting the scent

The reason we can smell the things around us is due to tiny molecules of that substance evaporating into the air (they are volatile molecules) and moving into our noses. Once in our noses, these tiny molecules bind to receptors (called olfactory receptors) and trigger a complex series of events, leading to our brain interpreting this as a smell. The average human nose contains around 5 million of these olfactory receptors, whereas the nose of our canine friends have around 220 million! This huge number of receptors is what makes dogs so good at smelling, and perhaps why it would seem that they are able to “sniff out” cancers.

The reason we can smell the things around us is due to tiny molecules of that substance evaporating into the air (they are volatile molecules) and moving into our noses. Once in our noses, these tiny molecules bind to receptors (called olfactory receptors) and trigger a complex series of events, leading to our brain interpreting this as a smell. The average human nose contains around 5 million of these olfactory receptors, whereas the nose of our canine friends have around 220 million! This huge number of receptors is what makes dogs so good at smelling, and perhaps why it would seem that they are able to “sniff out” cancers.

How does cancer smell?

(No, this isn’t a pun!) I’ve mentioned that we perceive things to smell due to tiny molecules from that object diffusing into our nose and binding to olfactory receptors. But how does cancer go about giving off a smell that can be detected by dogs but not humans?

Scientists have shown that certain unusual volatile molecules are given off by various cancers – molecules that diffuse out from the tumour and can be detected by the receptors in a dog’s nose for example. As dogs have a much more sensitive sense of smell than humans, they are able to detect these molecules whereas humans cannot. Much like how we police train dogs to recognise the smell of missing persons, narcotics and even explosives, the dogs can be trained to look for these molecules given off by tumours (called biomarkers). When these biomarkers are detected, in a patients urine for example, the dog will act in a way that the handler knows the dog has found what it is looking for – in doing so, predicting that the patient has a tumour. In Frankie’s case, he was trained to lie down if he detected “the smell of thyroid cancer”, or to turn away if the urine sample did not contain any cancer biomarkers.

So just what is Frankie smelling?

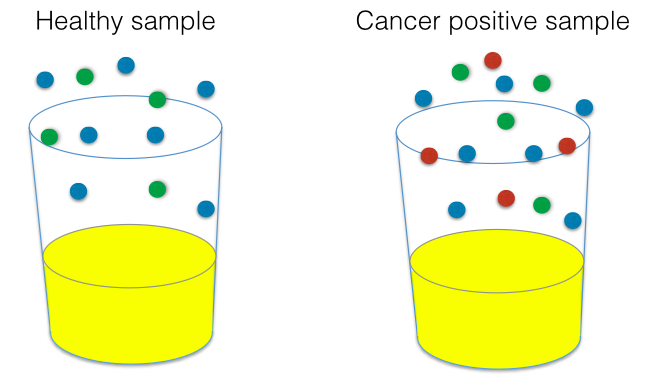

Unfortunately, this is where science falls short. We know that various tumours give off different “smells”, but it is the precise molecule that is unique to cancers that we are not quite sure of. Frankie was trained to detect thyroid cancers by being presented with urine samples of patients known to have thyroid cancer, as well as samples from healthy people (acting as a control group). When presented with a cancer positive sample, he was taught to lie down, and then given a treat to reinforce this behaviour. When the sample was cancer free, he was taught to turn away, and again given a reward. This process was repeated over and over again, a process known as conditioning, so that Frankie learnt to pair the smell of cancers with lying down (and of course getting a tasty treat), and the smell of healthy urine with turning away.

If we could isolate the exact molecule it is that Frankie is smelling (in the example above, the red molecule), it could be possible to develop so-called E-noses: electronic devices that could be used to detect the presence of certain volatile molecules, including molecules present in cancers. Research in this area is still in early days, but seems to be very promising. In fact, E-noses have been used already to successfully detect a type bacteria, called C. difficile, in the faeces of infected patients. This is possible as scientists know which volatile molecules are given off by the bacteria, hence they can make a device to look for this molecule. If this were possible for cancers, it could allow for serious improvements in early diagnosis, ultimately leading to a better chance of survival for cancer patients. I knew there was a reason why I have always loved dogs.

Love this post, absolutely fascinating! Definitely going to keep a dog with at all times so it can warn me if I am getting sick.

LikeLike

Really loved this! SO fascinating! Answered all my questions 🙂 dogs are great!

LikeLike